Competition-law specialists at Primerio have compiled the following snapshot of 2025.

Competition law enforcement across Africa continued its market trajectory of expansion throughout 2025, with early signals in 2026 enforcing a continent-wide shift towards more assertive, coordinated and policy-driven antitrust regulation. At both a national and regional level, authorities have increasingly moved beyond traditional enforcement and investigative tools.

A defining feature of 2025 has been the growing institutional confidence of African regulators. From the introduction and strengthening of regional regimes to the imposition of significant sanctions against multinational digital market players, African Antitrust enforcement bodies have demonstrated both technical capacity and willingness to ensure compliance with regional and national legislation. At the same time, legislative reform and increases in guidance notes and clarificatory tools signal an increasingly sophisticated regulatory environment, however, one which is more complex for multi-jurisdictional transactional and conduct risk.

This Snapshot spans the key developments we have previously reported on across Southern Africa, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (“COMESA”), the Economic Community of West African States (“ECOWAS”) and the East African Community (“EAC”), highlighting recent enforcement trends, institutional milestones and new policy innovations that shaped 2025 and which we anticipate will define the African Antitrust landscape as we move further into 2026.

Southern Africa

In South Africa, 2025 and early 2026 have been characterised by increasing interventions in mergers as well as continued use of exemptions and industrial policy.

Digital platform regulation was a defining theme in 2025. The South African Competition Tribunal’s (“SACT”) interim relief order in the Lottoland / Google Ads case signalled a willingness to ensure enforcement over exclusionary conduct in online advertising. This assertiveness was echoed in the GovChat v Meta ruling, where the SACT’s approach to platform access and data inoperability signalled the intention to rest the outer bounds of abuse of dominance enforcement against global big-tech firms.

In parallel, South Africa saw emerging scrutiny from the consumer protection angle, with the South African National Consumer Commission probing e-commerce platforms’ data practices and compliance frameworks, highlighting the convergence between competition and consumer protection enforcement in digital markets.

The South African Competition Commission’s (“SACC”) media and digital platforms market inquiry outcomes, as well as the Google’s agreement to pay ZAR 688 million to South African media, have further illustrated how negotiated remedies and sectoral interventions are being deployed to rebalance digital value chains.

Exemptions and block exemptions have remained a central tool available to parties in South Africa. The granting of Transnet’s 15-year exemption raised significant debate about the appropriate balance between enabling infrastructure coordination and preserving competitive neutrality. Subsequent developments in exemptions, including the block exemption in respect of Phase 2 of the Sugar Master Plan and corridor-based logistic exemptions, confirm that exemptions are being embedded as a long-term sector restructuring tool rather than temporary measures to allow coordination as well as a means to attain specific public interest and industrial policy goals.

Procedural and evidentiary developments have also shaped the landscape. The SACT’s decision granting absolution in the X-Moor tender cartel case clarified the evidentiary burden in collusive tendering prosecutions, reinforcing the need for robust inferential and documentary proof.

In relation to developments in merger control proceedings in South Africa, intervention dynamics were tested in Lewis Stores application to intervene in the merger between Pepkor Holdings Limited and Shoprite Holdings Limited. The South African Constitutional Court permitting Lewis’ intervention have raised much debate as to whether intervention by third parties frustrates and unduly delays the finalisation of merger hearings in South Africa.

The SACC had introduced a number of guidelines in relation to treatment of confidential information, as well as gatekeeper conduct with respect to pre-merger filing consultation processes, online intermediate platforms, notifications of internal restructures meeting the definition of mergers, and price-cost margin calculations. More recently, there have been proposed revisions to the SACC’s merger thresholds and filing fees, signalling a move towards greater ease in deal negotiation.

COMESA

2025 was a landmark year for both regulatory and enforcement developments in the COMESA region.

Most significantly, 2025 saw the introduction of the newly renamed ‘COMESA Competition and Consumer Commission” (“CCCC”) and the publication of the much anticipated COMESA Competition and Consumer Protection Regulations (2025). Early 2026 has also brought subsequent clarifications released by the CCCC with regard to its new suspensory merger regime in order to provide further insight into the CCCC’s approach in regulating mergers now brought to its attention.

The COMESA Court of Justice’s decision regarding the legality of safeguard measures imposed by Mauritius on edible oil imports from COMESA Member States demonstrated continued willingness of regional bodies policing activities of individual Member States.

Regional integration has been further reinforced through a number of cooperation initiatives, including formalised engagement between COMESA and the EAC on competition and consumer protection enforcement.

At Member State level, national competition regimes continue to interact dynamically with the regional system – this has been demonstrated by merger control retrospectives in Malawi, and regulatory developments in Zimbabwe. The Egyptian Competition Authority has, through recent guidance, also sought to provide further clarity with respect to its merger control regime and align with international best practice.

When considered alongside reflections on enforcement trajectory more broadly throughout the COMESA Common Market, the CCCC appears to be consolidating a far more assertive and procedurally sophisticated authority.

EAC

The operational launch of merger control marked a structural milestone for the East African Community Competition Authority (“EACCA”). The EACCA’s confirmation that it would begin receiving merger notifications from November 2025 introduced yet another operational regional authority on the African continent.

National enforcement has remained active alongside this regionalisation. Tanzania’s merger control developments and enforcement strategy signal a regulator seeking sharper investigative tools and clearer procedural pathways. Institutional cooperation is also deepening, as evidenced by alignment initiatives between the Tanzania Fair Competition Commission and the Zanzibar Fair Competition Commission, aimed at reducing jurisdictional fragmentation.

Kenya has also provided some of the region’s most visible enforcement signals. The upholding of cartel sanctions in the steel sector confirms judicial backing for robust cartel penalties. Leadership transitions at the Competition Authority of Kenya may also influence enforcement measures leading into the new year. More recently, the fine imposed in the Directline decision underscores the reputational and financial stakes attached to non-compliance with Kenya’s competition regime.

ECOWAS

Nigeria has been at the forefront of digital enforcement measures in Africa. The Nigerian Competition and Consumer Protection Tribunal’s landmark decision upholding the Federal Competition and Consumer Protection Commission’s $220 million fine on WhatsApp and Meta for discriminatory practices signals both the scale of sanctions now at play.

Regionally, the Economic Community of West African States Regional Competition Authority (“ECRA”) merger control regime gained operational depth in 2025, having been launched in late 2024. Early analysis framed the regime as a foundational shift towards increased regional review, while subsequent approval decisions demonstrated increasing practical application and institutional learning.

Legislative reform also remains underway at Member State level. The Gambia’s draft competition bill reflects a move towards more proactive market inquiry and enforcement powers, suggesting that more novel African national regimes are evolving in tandem with regional frameworks.

Conclusion and Outlook for 2026

Across the African continent, several cross-cutting themes have emerged. First, in line with global antitrust enforcement, digital market investigations and enforcement remains a focus point. From South Africa’s media and digital platform market inquiries and exclusionary investigations to Nigeria’s abuse of dominance sanctions and COMESA’s recent investigation into Meta, it is apparent that African competition authorities are increasingly asserting jurisdiction over digital platforms. Second, exemptions and public interest tools, particularly in South Africa, are being normalised as structural industrial policy instruments.

Regionalisation is also accelerating. COMESA’s long-awaited regulatory overhaul, the introduction and operationalisation of the EACCA’s merger regime and ECOWAS’ expanding enforcement collectively point towards a multi-layered African merger control framework requiring often complex, parallel and overlapping multi-jurisdictional navigation. Institutional cooperation agreements and memorandums of understanding further reinforce this trajectory, suggesting more coordinated enforcement and increased risk of detection.

Looking ahead, we note three developments which merit close attention. First, the practical implementation of new regional regulations, specifically those of the CCCC in COMESA, will test capacity, compliance as well as appropriateness of new regulatory hurdles in the global M&A space. Hand in hand with these, overlapping regional bodies will likely lead to jurisdictional disputes. Second, Digital market remedies are likely to evolve. Finally, in line with recent developments elsewhere, the continued blending of competition, consumer protection, and industrial policy objectives suggest that African antitrust enforcement will remain uniquely pluralistic.

By the Editor

COMESA’s long-delayed and much-anticipated publication of the new 2025 Competition and Consumer Protection has prompted much fanfare, and rightfully so. It represents a potential turning point and coming-of-age for the now 12-year old regional antitrust regulator.

We decided to swim against the current and, rather than focus exclusively on “COMESA 3.0,” take a look back at the past year, so as to better gauge the (now) CCCC’s future performance versus its immediate past.

Fortuitously, our editor was present at a gathering of the ‘Fourth Estate,’ convened in Nairobi by COMESA’s Dr. Willard Mwemba. For the third consecutive time, the Commission had invited members of the press to present its successes, show off the tight relationships between its staff and that of other national authorities (of note, David Kemei, Director General CAK, chairman of the EACA and local host, was present for most of the event, as was of course the agency’s éminence grise, Dr. George Lipimile), and to remind the assembled journalists that, in the bigger picture, the agency’s AfCFTA competition protocol coordination remained ongoing — more on that another day…

Without further ado, here are the 2025 COMESA highlights, as selected by the Commission:

Mergers

The large francophone-anglophone broadcasting deal of Canal+ acquiring Multichoice presented “lots” of competitive concerns according to Dr. Mwemba. Already dominant firms merging to form an even larger entity was a serious threat to broadcast competition. Multichoice’s past behavior of refusing sublicenses and threatening to leave certain markets showed its unparalleled dominant position in various COMESA submarkets. The parties did compete head-on with head other in three jurisdictions, Rwanda, Madagascar, and Mauritius, and would have had a foreclosing position COMESA-wide in relation to super premium content, leading the (then still) CCC to seek prohibition of the merger, and at a minimum the survival of Multichoice (and its “Talent Factory”) as an independent entity and employer in the region.

The parties’ defense relied in part on arguments alleging subscriber losses, eventually resulting in a conditional approval by the CCC with several commitments of the parties.

Two failure-to-file violations stand out in the past year: The Bosch/Johnson Control deal drew a failure-to-file violation of the (much maligned and soon to be replaced under the new Regulations) “30-day rule”. Interestingly, the fine was reduced from a significant $400,000 initial amount to an almost negligible $8000, as JCI (the target and a first-time offender entitled to a 30% fine reduction) was to blame for the “inadvertent” false company statistics Bosch used to calculate whether the filing threshold was met. While challenged by the acquirer, Bosch received a symbolic $1 fine for its own negligence in failing to vet the target’s figures for purposes of determining notifiability.

In the Mauritian BRED/BFV banking transaction, the fine was significantly reduced by the acquirer’s cooperation, minority shareholding status in many subsidiaries, and first-time offender status, resulting in merely $28,005 initial F2F fines.

On a broader scale, looking to the newly established EAC competition regime and its merger notification requirements, Dr. Mwemba recognized the concern that dual notifications will occur in all likelihood for the foreseeable future.

Anticompetitive Practices

The Commission’s standout case this past year was doubtless the “beer matter”: three main areas of concern stood out in the Heineken case, in which the respondent was found to be dominant in various geographic markets. The three issues were: single-branding (foreclosing competing products at the downstream distribution level), absolute territorial restrictions (prohibiting distributors from not only active but also passive selling into unauthorized regions), and resale price maintenance (imposing a firm price — or here, a fixed profit margin — on resellers of the products). A long lasting case, from June 2021 until early September 2025, resulting in a settlement procedure, eliminating the three clauses of concern and imposing the maximum settlement amount of $900,000 on Heineken. Of note: Beer makers are also subject to an ongoing CCC investigation into the cross-shareholdings of various manufacturers.

Similarly, the Commission accused Diageo of the same types of anticompetitive practices in several COMESA member states. As the respondent had stopped one of the offending types of conduct (RPM) prior to the investigation’s commencement, the final combined fine amount was reduced to $750,000.

A further territorial restriction investigation into Toyota’s distribution practices is ongoing and “at an advanced stage”, with the CEO expecting to close the matter by Q1/2026. Finally, the CCC is evaluating the effects of, among other things, Coca-Cola’s unilateral single-branding rules against retailers stocking only its own products in branded refrigerators, which can result in effective foreclosure of competing brands, especially at small retail businesses with limited floor space allowing only a single fridge.

Consumer Protection

The airline sector did not escape the CCC’s enforcement net, as British Airways/Qatar experienced in the recently concluded investigation into Nairobi-London route collaboration among the parties, which they claimed allowed them to increase the volume of flights to 28 per week and lower ticket prices. The CCC permitted the conduct for a limited time of 5 years, requiring the parties to provide proof of the alleged efficiencies within two years.

On the consumer protection front, the CCC was heavily focused on the air travel sector over the past reporting year. It will publish, on Monday coming, a report detailing the results of its year-long airline survey and study, undertaken in conjunction with the African Union’s airline regulator.

Its signature agriculture study program, the African Market Observatory, continues to be funded and operationally supported by the Commission, having provided a key report to the COMESA Council of Ministers. This effort has also led to the ICN having awarded the running of its agriculture program to the Observatory. Dr. Mwemba proudly highlighted that the CCC assisted in averting a potential hunger crisis, namely in an (unpublished, we presume) maize case involving a sovereign engaging in absolute territorial restrictions, threatening serious food insecurity in Eswatini; it was the CCC’s advocacy efforts, as opposed to a full-fledged investigation, that yielded the positive results.

Finally, the CCC also concluded its drafting of a unified Model Consumer Protection Law, to serve as a standardized & harmonized guideline for African countries. This comes as part of an effort to eradicate the fragmentation of competition and consumer protection laws, seeking the eradication of harmful corporate conduct and non-tariff trade barriers.

Looking Ahead: What’s in Store for COMESA 3.0?

Diverging from the titular “retrospective,” it appears fitting to step forward into the present moment and look ahead, with the Commission’s recent successes under its former Regulations now firmly established. To do so, I will quote from an article Dr. Liat Davis and I recently published in the Concurrences journal, entitled “Refining Regional Rapprochement: COMESA’s Competition Enforcement Comes of Age“:

The Mwemba era (2021 – present) has both accelerated and consolidated these earlier reforms, contributing to increased confidence in the regime among international stakeholders. With the exception of a temporary pandemic-related decline, merger activity has continued to rise, surpassing 500 notifications to date and now including the Commission’s first enforcement against gun-jumping. Non-merger enforcement has also expanded, with 45 conduct investigations and at least two cartel cases initiated. In parallel, the Commission has entered into numerous Memoranda of Understanding and multilateral cooperation agreements with African and global counterparts, strengthening its external partnerships. At the regional level, the CCC has acted as a catalyst for the establishment and development of National Competition Authorities (NCAs), offering indirect financial support, training, and collaborative initiatives.

This iterative process of course correction and capacity-building is now culminating in the long-awaited revision of the primary legislation. The new CCPR, due to take effect at the end of 2025, will formalize the Commission’s expanded mandate. In light of the extensive reforms embodied in the new CCPR, and consistent with the prior informal designation of the CCC’s post-2021 period as “COMESA 2.0,” the implementation of the CCPR will mark the beginning of a third phase in the regime’s evolution. Appropriately described as “COMESA 3.0,” this stage is expected to be characterized by the following key attributes:

- Expanded unilateral-conduct enforcement, owing to increased staffing, sustained capacity-building, and growing experience in conduct and cartel cases;

- A significant rise in cartel investigations, driven principally by the forthcoming leniency regime;

- Higher merger volumes, resulting from the move to a suspensory filing regime and accompanied by a likely increase in conditional approvals (subject to wider global economic conditions); [note: the CCC’s statistical trajectory is already sloping upward, as it has reviewed approximately the same number of transactions in the past 4 years as it had in the first 8 years of its existence.]

- Strengthened consumer-protection enforcement by the ‘CCCC’, reflecting the Commission’s broadened mandate and aligning with wider African competition-law trends, including South Africa’s increasing incorporation of public-interest factors in merger analysis and Nigeria’s FCCPC using data-protection grounds to impose record fines; and

- The development and application of a carefully delineated “public interest” standard in competition cases, subject to strict guardrails to prevent politicization and adapted to the unique constraints of a multi-national enforcement regime.

By Daniella de Canha and Megan Armstrong

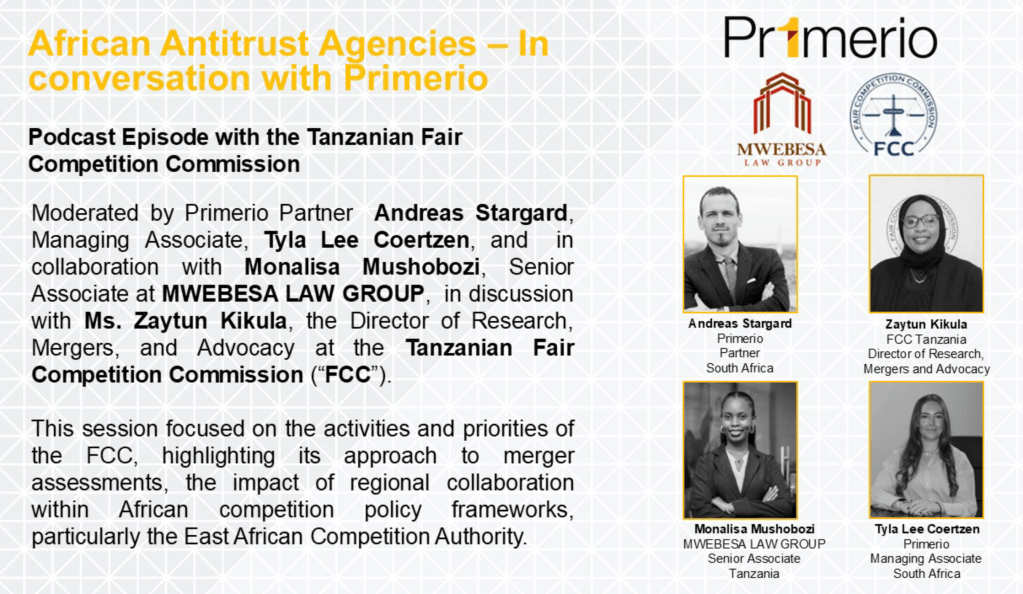

On 18 August 2025, pan-African competition-law boutique firm Primerio continued its “African Antitrust Agencies – In Conversation” series, casting a light on the Tanzanian Fair Competition Commission (“FCC”) in a dynamic exchange which analysed merger control practices, regional competition enforcement and regulatory reform. The discussion featured Director of Research, Mergers, and Advocacy at the FCC, Zaytun Kikula, in conversation with Primerio Director, Andreas Stargard, Primerio Associate Tyla Lee Coertzen, and Advocate at Mwebesa Law Group, Monalisa Mushobozi. You can watch a recording of this session here.

Ms. Kikula highlighted that the FCC’s focus has thus far mainly been on mergers, as well as investigating the dominance of abuse and cartels. She also points out that the FCC have been very active in its merger control regime, handling between 50 and 70 filings annually. Most of the notified transactions are smaller, spanning across sectors from telecommunication, finance, manufacturing, mining and insurance. Ms. Kikula stated that the recent amendments made to the Fair Competition Act 2024, have created a shift in merger reviews. Before these changes, the focus was only market share, whereas now mergers are being evaluated through a broader lens.

Monalisa noted an amendment to the Act now allows for a merger to be approved even it is strengthens the position of a dominant firm, provided the transaction yields a demonstratable public interest benefit. Ms. Kikula further explained that while the FCC has not received a transaction which triggers the above-mentioned amendment, notified transactions are subject to a 14-day notice period which invites commentary in order to ensure that the concerns of the public are adequately considered.

The FCC has encountered numerous instances of unnotified mergers, some voluntarily disclosing these transactions to the FCC, after the fact and others through investigation by the FCC. The FCC engages with these firms and lets them know that if they do not notify the Commission and proceed, this will constitute an offence which is punishable by a fine of between 5% and 10% annual turnover. Ms. Kikula mentioned the FCC assumes the role of a business facilitator and encourages settlements where the firms pay a filing fee as well as an additional settlement fee for instances of non-compliance. Filing fees are determined by the structure of the transaction, for instance, when dealing with a global entity the fees are calculated based on global turnover. When the transaction is domestic fees are calculated based on local turnover. She also pointed out the fact that this fee calculation is unconditionally governed by law and that there is no room for negotiation.

Monalisa mentioned that the law stipulates that the Commission has 60 days to approve the merger and inquired whether there have been cases where this timeframe has been shortened or extended. Ms. Kikula explained that non-complex merger reviews can extend between 30 to 45 days, however, in some cases can extend to 90 days. Noting that it may go up to 135 days, the statutory maximum. With regards to remedies, the FCC typically imposes behavioural conditions which are tailored to the specific sector involved.

The regional integration of competition law across Africa was a key theme which was highlighted. Andreas brought to the listeners attention that the East African Community Competition Authority (“EACC”) will be coming online in November of this year and will be open to receiving merger notifications. She further expressed that dual filings should be avoided in order to lessen confusion, emphasising the importance of confidentiality under a Memorandum of Understanding in order to protect information. Ms. Kikula discussed the two upcoming regulatory reforms which the FCC is in the process of introducing, with the first being a leniency program and the second being specific regulation for the assessment of dominance. She further noted that the threshold for market share has increased from 35% to 40%. This expansive discussion highlights the FCC’s ability to balance application with facilitation, making it a driving force in East African competition law.

By Michael Williams

Introduction

The Competition Commission of South Africa (“the Commission”) released a Cost-of-Living Report (“The Report”) on 4 September 2025, setting out a structured, data-driven assessment of affordability pressures faced by South African households, with particular focus on those low-income consumers predominantly impacted by consistently high inflation rates. Its aim is to provide insights into the affordability of basic goods and services so that individuals, households, businesses, and policymakers can assess financial capacity and understand how price movements affect living standards. This is in alignment with the Presidency’s Strategic Plan that identifies tackling the high cost of living as a priority.

The current cost-of-living crisis is framed against entrenched domestic challenges, rising food, fuel and electricity prices against the backdrop of an ongoing energy crisis and interest rate increases that have lifted debt servicing costs in an environment where growth in household income has maintained the same pace.

Background and Goal of the COL Report

The COL Report stems from the Commission’s earlier Essential Food Price Monitoring (“EFPM”) programme, first published in July 2020 to track the prices of staple foods across the value chain, from farm to retail, and to analyse price transmission between producers, processors and retailers. Recognising shifting expenditure patterns and growing inequality, the Commission has expanded the scope of the EFPM, rebranding it as the COL Report. The new format retains essential food price monitoring while including those key non-food items that have a significant impact on lower income households.

As James Hodge, the chief economist at the Commission said:

“This analysis plays a crucial role in identifying the economic pressures various socio-economic groups, particularly low-income households, experience in a time of fluctuating prices and growing inequality.”[1]

The COL Report’s overarching intent is to highlight the affordability of basic goods and services in South Africa and to identify the underlying drivers of the cost-of-living crisis.

The COL Report tracks non-food necessities (e.g., electricity, water, rentals, healthcare, minibus taxi fares and petrol, funeral policies, public school fees, and internet usage costs) alongside essential food items such as pilchards, eggs, IQF chicken, brown bread, sunflower oil, maize meal. It further illustrates interest-rate effects by comparing owner’s rent as an equivalent to bond repayments on a standard mortgage. This structured monitoring enables the Commission to highlight where inflation is concentrated, where pricing appears sticky during cost reductions, and where spreads are widening.

COL Report and South African competition law

While the COL Report does not draw conclusions in respect of anticompetitive conduct, it does have notable implications for competition oversight by continuing to apply the Consumer’s International Early-Warning System (“Early-Warning System”) and evidentiary baseline for price transmission across essential value chains.[2] Several features are salient for competition law practice and policy, as drawn directly from the Report’s findings and methodology:

A broadened monitoring mandate across non-food essentials, expands the EFPM’s food focus to include electricity, water, rentals, transport, primary healthcare, funeral policies, education, and internet costs, the Commission positions itself to track persistent inflation drivers where administered pricing or sectoral structures may entrench affordability constraints. Assisting in the prioritisation and policy engagement across markets that shape consumer welfare, even where formal competition enforcement is not immediately implicated.

It presents clear analytical boundaries that respect competition law standards. It expressly cautions that the analysis of spreads (aggregate spread between retail and producer prices) is not an inference of anticompetitive conduct. Instead, spreads are diagnostic of price transmission and places in the chain where margins are expanding. The Commission’s reliance on the Early-Warning System underscores that the COL Report is an intelligence and monitoring tool, useful for triage and prioritisation, rather than a determinative finding of collusion or abuse. This delineation aligns with competition law’s evidentiary requirements while still highlighting areas that may merit closer scrutiny.

The Report identifies pricing patterns relevant to oversight, documenting patterns in essential staples where input costs fell or stabilised, but retail prices remained elevated. An example of this is, for instance, the discussion of eggs, sunflower oil, and maize meal, where price stickiness and widening retail margins are observed at various points. In brown bread, producer-level margins rose as wheat prices declined, and retail margins fluctuated as retailers alternated between absorbing and passing through cost movements. Such documented patterns inform areas where the Commission may, in being consistent with its mandate, monitor for potential strategic pricing behaviour over time.

The contextualisation of administered prices as structural inflation drivers, by the Report identifies evidence that electricity prices rose 68% and water prices rose 50% over the last 5 years. This is well above headline inflation and provides a policy context for sustained consumer-facing cost pressure. Although administered tariffs are not set through ordinary market dynamics, persistent increases affect downstream markets and household welfare, which are central concerns of the Commission’s broader public-interest and competition policy ecosystem.

The Report recalls that, following the Commission’s Data Services Market Inquiry in 2019, mobile data prices fell significantly in 2020 and 2021 and have remained comparatively stable. This illustrates how evidence-based monitoring and market inquiries can produce effective outcomes, a tool that the Commission may use in other sectors flagged by the COL Report.

The Report uses an interest rate lens to complement the Consumer Price Index (“CPI”) measures of housing costs, by comparing bond repayments (up 28% over the period 2022 to March 2025) with owner’s equivalent rent, shows how debt-servicing costs meaningfully diverge from CPI’s treatment of owner-occupied housing. This perspective assists competition authorities and policymakers to understand consumer budget constraints that can interact with the market.

Collectively, these features show that the COL Report is intended to guide monitoring and policy dialogue, highlight potential risk zones, without asserting contraventions and maintain an evidentiary base for any future work within the Commission’s statutory toolkit such as market inquiries.

Key Findings Highlighted in the Report

To ground the above effects in the Report’s data, the COL Report records the following notable movements over the past 5 years for the period of 2020 to March 2025:

Key non-food items:

Essential foods:

These findings supply concrete price-formation signals, where margins compress, where they expand, and how quickly costs are transmitted, which are central to the Commission’s ongoing monitoring orientation.

In Conclusion, the COL Report documents a pronounced squeeze on South African households, especially the poorest, driven by elevated inflation in essential services and persistent cost pressures. It demonstrates that while certain categories (e.g., rentals, funeral policies) have increased less than headline inflation, others (e.g., electricity, water, education, and several staple foods) are coming down hard on budgets. In parallel, the COL Report records instances of sticky pricing and widening spreads, and it maintains a clear line between diagnostic monitoring and legal inference.

For competition law and policy, the COL Report delivers three practical gains, by widening the scope to include key essentials beyond food, showing the spreads and pass through clearly, and a continuation of the Early-Warning System. Furthermore, it assists the Commission in fulfilling its mandate by flagging areas which may need attention, guiding debate on administered prices, and grounding future market work in carefully, publicly sourced data.

[1] https://www.citizen.co.za/business/personal-finance/new-cost-of-living-report-shows-battle-of-being-a-consumer-in-sa/

[2] https://www.consumersinternational.org/what-we-do/good-food-for-all/fair-food-price-monitor/

[3] https://www.nersa.org.za/electricity/pricing.

[4] Statistics South Africa (StatsSA) Consumer Price Index: Sources and Methods. February 2025. Available [Online] https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-01-41-01/Report-01-41-012025.pdf.

[5] https://iol.co.za/mercury/news/2024-10-08-big-increases-in-sa-medical-aid-fees-causes-alarm/.

[6] https://www.sabcnews.com/sabcnews/taxi-alliance-says-fuel-price-maintenance-costs-contributed-to-latest-fare-hike/.

[7] https://www.moneyweb.co.za/news/south-africa/buckle-up-parents-school-fee-hikes-outpace-inflation/.

[8] Bi-Annual-Tariffs-Analysis-Report-Q2-2022-23- Abridged.pdf

[9] Competition Commission South Africa Cost of Living Report – August 2025, page 17.

[10] Competition Commission South Africa Cost of Living Report – August 2025, page 20.

[11] Competition Commission South Africa Cost of Living Report – August 2025, page 21.

[12] Competition Commission South Africa Cost of Living Report – August 2025, page 22.

[13] Competition Commission South Africa Cost of Living Report – August 2025, page 23.

[14] Competition Commission South Africa Cost of Living Report – August 2025, page 25.

By Megan Armstrong and Amy Shellard

On 5 June 2025, Primerio hosted the latest instalment of its African Antitrust Agencies – in Conversation series. This session featured Primerio’s Managing Associate, Joshua Eveleigh, alongside Carole Bamu, Primerio’s in-country lead partner for Zimbabwe, and Calistar Dzenga, Head of Mergers at the Zimbabwe Competition and Tariff Commission (“CTC”). Their wide-ranging conversation offered a rare window into Zimbabwe’s merger control regime, recent enforcement developments, and anticipated legislative reforms, thus providing valuable insight into how the regulator is intensifying oversight and sharpening enforcement.

Calistar Dzenga explained that any transaction meeting the combined turnover or asset threshold of USD 1.2 million in Zimbabwe is notifiable under the Competition Act [Chapter 14:28]. Notably, this includes foreign-to-foreign mergers, the activities of which have an appreciable effect within Zimbabwe’s market, a critical point as Zimbabwe becomes an increasingly active jurisdiction in African dealmaking. The CTC’s review process starts with notification and payment of fees capped at USD 40,000, followed by detailed engagement including market research and stakeholder consultations.

Mergers are classified as either “small” or “big,” with smaller transactions typically decided within 30 days, while larger or complex deals taking up to 90 to 120 days.

While the CTC uses indicators like the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) as screening tools, the CTC confirmed that market shares are not determinative on whether a transaction will have anticompetitive effects. Instead, the CTC focuses on, and considers, barriers to entry, countervailing buyer power, and the historical context of collusion. Zimbabwe’s framework embeds public interest considerations within competition analysis, differing from South Africa’s dual-stream approach.

Public interest concerns, particularly employment protection and local industry support, are increasingly central to merger decisions. These conditions often require maintaining junior-level employment for at least 24 months post-merger and increasing local procurement. Industrial development goals also shape decisions, including mandates for mineral beneficiation in sectors such as lithium processing.

One of the most significant recent cases involved CBZ Holdings’ attempt to acquire a controlling stake in ZB Financial Holdings. The proposed merger raised alarms over market concentration in banking, reinsurance, and property, as well as risks to consumer choice. After extensive engagement, the Commission proposed strict conditions, from divestitures in related markets to commitments to maintain separate brands. Ultimately, the merging parties walked away, demonstrating that Zimbabwe’s regulator has the resolve to stand firm even on high-profile deals.

Joshua and Carole explored how Zimbabwe’s CTC collaborates with other African authorities. Calistar highlighted the strong relationships the CTC has with theCOMESA Competition Commission, the South African Competition Commission, as well as the relevant competition authorities in Zambia and Botswana. Such cross-border collaboration plays a crucial role in ensuring that mergers do not slip through regulatory gaps and that decisions are coordinated across the region. The CTC also uses memoranda of understanding with other national regulators, such as the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange and the Reserve Bank, to detect transactions which have not been notified to the CTC.

A major theme of the conversation was the long-awaited Competition Amendment Bill, which is set to overhaul Zimbabwe’s 1996 Act. As Calistar explained, the Amendment Bill will:

(i) give the CTC powers to impose harsher administrative penalties for restrictive practices and cartels;

(ii) introduce clearer rules on public interest considerations;

(iii) allow the CTC to conduct proactive market inquiries rather than just reactive investigations;

(iv) enable anticipatory decisions for failing firms to speed up urgent cases; and

(v) provide leniency frameworks for companies disclosing collusion.

The reforms are expected to give the CTC more enforcement capability and help align Zimbabwe with international practices. Joshua mentioned that these changes would give the CTC “more teeth to bite,” a phrase Calistar repeated, showing how the regulator wants to align with global standards.

Right now, Zimbabwe is seeing more merger activity, especially in the financial services and manufacturing sectors. This is predominantly due to consolidation pressures, along with large infrastructure projects. With regulatory scrutiny picking up speed, companies really have to stay on the front foot when it comes to managing clearance risks and be ready for stricter enforcement.

Joshua also pointed out that it’s an exciting period for competition law in Zimbabwe. He believes businesses should start preparing now for the significant changes that are on the horizon. For Primerio’s African antitrust team, this conversation really highlights how important it is to guide clients through an evolving and complex enforcement landscape.

To view the recording of this session, please see the link here.

By Matthew Freer & Michael Williams

Introduction

South Africa’s logistics and freight infrastructure stands at a critical crossroads, with persistent inefficiencies in the rail, port, and road sectors posing a significant threat to the country’s economic competitiveness and growth. In response to this crisis, the government has introduced the Block Exemption for Ports, Rail and Key Feeder Road Corridors which came into effect on 8 May 2025, a landmark regulatory intervention under the Competition Act 89 of 1998 (the “Act”), spearheaded by Trade, Industry and Competition Minister Parks Tau (Government Gazette No. 6182, 2025). This block exemption represents one of the most substantial reforms in South Africa’s competition law landscape, specifically designed to enable greater collaboration among firms operating in the logistics value chain, while still safeguarding against anti-competitive conduct.

The exemption, notable for its 15-year duration, signals the Government’s commitment to long-term, structural support for revitalising the country’s logistics backbone. It allows companies in the transport infrastructure and logistics sectors to apply to the Competition Commission for permission to coordinate efforts aimed at addressing operational inefficiencies, infrastructure capacity shortages, and systemic breakdowns in port and rail infrastructure, all while complying with relevant sector laws and policies. This marks a decisive shift from the traditional competition law approach, which generally prohibits coordination among competitors, to recognise that South Africa’s logistics crisis requires extraordinary, collective action.

Minister Parks Tau’s role has been pivotal, as he gazetted the exemption to promote collaboration that can reduce costs, improve service levels, and minimise losses caused by years of underinvestment and mismanagement in the logistics sector. There is a clear and urgent economic basis for the intervention supported by the fact that South Africa is estimated to lose as much as R1 billion per day due to freight system failures, with follow on effects across production, manufacturing, wholesale, retail, and export sectors (“A billion a day – that’s what SA loses through freight failures”, Freight News, 21 May 2024). Congestion at major ports, a deteriorating rail network, and poorly maintained road corridors have not only undermined daily business operations but have also eroded the country’s position in the broader global trade industry.

By enabling coordinated, pro-competitive solutions-subject to strict oversight and clear exclusions for cartel conduct, the block exemption aims to unlock investment, restore critical infrastructure, and lay the foundation for a more resilient, efficient, and globally competitive logistics system.

Background/History

South Africa’s ports and rail infrastructure have historically suffered from inefficiencies and significant decay, impacting the country’s logistics and economic performance. The rail network, largely completed by 1925, faced underinvestment from the late 20th century onwards, leading to deteriorating rolling stock, signalling, and track conditions. This decline was arguably caused by theft, vandalism, and outdated systems, most notably within Transnet Freight Rail, which has struggled with equipment shortages and infrastructure damage, including cable theft and adverse weather events such as the 2022 KwaZulu-Natal floods (Dr Mitchell, The Rise and Fall of Rail, Chapter 4). Ports like Durban and Cape Town, originally designed for mostly rail cargo, now face congestion and aging infrastructure challenges, with cranes and gantries exceeding their intended lifecycle, further slowing cargo handling and export throughput. These events trigger a bottleneck for resources waiting to be exported.

To address these challenges, privatisation is often proposed as a solution. However, previous reform efforts including partial privatisation and initiatives to involve the private sector in infrastructure management have largely failed. These failures were primarily due to poor project management, cost overruns, and user resistance, as demonstrated by the Gauteng electronic tolling system. Recognising these shortcomings, the Government now seeks to mobilise private sector financing and expertise through public-private partnerships and concessions, with the goal of enhancing infrastructure delivery and operational efficiency (P Bond and G Ruiters, South Africa’s Failed Infrastructure Privatisation and Deregulation).

Previous key policy milestones that are aimed at addressing these problems include the Transnet Network Statement, which promotes open access reforms to rail infrastructure, the transport ministry’s Request for Information (“RFI”) to explore private sector involvement and innovative solutions, and now the Government Notice issued by Trade, industry & competition minister Parks Tau.

Legal Framework: The Competition Act

The Act ordinarily prohibits agreements between competitors that substantially prevent or lessen competition, with Section 4(1)(b) specifically prohibiting price-fixing, market division, and collusive tendering (Competition Act 89 of 1998, s 4(1)(b)). However, under Section 10(10) of the Act, the Minister of Trade, Industry and Competition may issue exemptions in the public interest Competition Act 89 of 1998, s 10(10). The newly gazetted 15-year Block Exemption for Ports, Rail and Key Feeder Road Corridors, is one such intervention. It permits limited coordination among firms in the logistics value chain to address critical inefficiencies, while maintaining prohibitions on core cartel conduct such as fixing selling prices or excluding small and historically disadvantaged market participants.

The exemption allows for collaboration on operational matters such as joint use of transport infrastructure, coordinated scheduling, and shared logistics data, activities that would typically contravene the Act’s per se prohibitions under Sections 4(1)(b)(i) and (ii). Importantly, each form of collaboration must be reviewed and approved by the Competition Commission, which retains oversight to ensure that such cooperation is pro-competitive, time-bound, and aligned with Competition Commission’s broader transformation and public-interest objectives. The exemption explicitly requires that such collaboration does not exclude new entrants or small, medium, and micro enterprises (“SMMEs”) and instead encourages inclusive participation.

However, the regulations expressly exclude cartel conduct. Section 4(1)(b)(i) and (ii) of the Act prohibits price-fixing, tender collusion, and market division, and these sections remain intact. Any coordination must be submitted for review to the Competition Commission, which will assess whether the collaboration is genuinely pro-competitive and in line with sector-specific goals and transformation mandates.

Rationale: Tackling a Logistics Crisis

The rationale behind the 15-year block exemption lies in its capacity to enable coordinated responses to mounting inefficiencies across the country’s rail, port, and road freight infrastructure, systems upon which the economy’s competitiveness rests.

A recent report by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) estimates that freight logistics failures cost the economy up to R1 billion per day, affecting production schedules, increasing costs, and undermining export reliability (“A billion a day – that’s what SA loses through freight failures”, Freight News, 21 May 2024). These issues are particularly acute in port terminals such as Durban and Cape Town, where backlogs have resulted in vessel queuing, delayed shipments, and significant demurrage charges.

The rail network, operated largely by Transnet Freight Rail, continues to degrade due to rolling stock shortages, cable theft, signalling issues, and adverse weather events (Transnet Integrated Report 2023). Following the 2022 KwaZulu-Natal floods, major lines experienced months-long disruptions, highlighting the vulnerability of logistics infrastructure (Presidential Climate Commission Brief on the 2022 KZN Floods, 2022). Moreover, a 2024 National Treasury report identified inadequate investment, operational inefficiency, and governance issues as long-standing contributors to the sector’s decline (National Treasury Annual Report 2023/24 (2024). In light of these challenges, the block exemption provides a legal framework through which firms can engage in limited coordination on logistics operations, such as the sharing of transport assets or the synchronisation of delivery schedules, without breaching competition laws.

The decision to set the exemption for 15 years rather than the more typical short-term period reflects a deliberate strategy to create regulatory certainty. Such long-term clarity is essential to attract private sector investment into joint ventures, infrastructure upgrades, and concessioning models. By providing a legally protected framework for collaboration, the exemption seeks to catalyse systemic reform and reduce South Africa’s long-standing overreliance on inefficient, state-controlled freight logistics.

Competition Analysis: Risk vs Reward

The exemption, while pragmatic, raises legitimate questions from a competition law perspective. One of the key risks is that, under the guise of coordination, dominant firms could entrench their market position and SMMEs and historically disadvantaged persons (“HDPs”). This concern is echoed by academic literature, which warns that crisis-driven exemptions, if not tightly monitored, can facilitate collusion and market foreclosure.

The block exemption also contains an explicit requirement that the collaborative measures must not undermine the participation of new entrants or black-owned logistics firms. In fact, they are encouraged to be integrated into these collective solutions, thereby aligning with the broader objectives of the Act, which focuses on inclusive growth and reducing economic concentration.

Internationally, temporary exemptions have been deployed during times of sectoral distress. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the European Commission issued Temporary Frameworks allowing certain forms of cooperation in sectors such as pharmaceuticals, food distribution, and energy, provided they were transparent, necessary, and time-limited (European Commission, Temporary Framework for State Aid Measures, 2020: 1–9). Similarly, the United Kingdom’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) granted exemptions in retail supply chains during 2020, illustrating how temporary coordination can maintain essential operations under stress (UK Competition and Markets Authority, Approach to Business Cooperation in Response to COVID-19, 2020).

Therefore, while there are inherent risks, the reward, a more functional, cost-effective, and inclusive logistics sector which outweighs the downsides if strict oversight is maintained. The exemption represents a calculated, legally bounded exception to orthodox competition principles, in the service of restoring one of the country’s most vital economic sectors.

Conclusion

The 15-year Block Exemption for Ports, Rail and Key Feeder Road Corridors represents a pivotal recalibration of South Africa’s competition law in response to an unprecedented logistics crisis. By permitting targeted, supervised coordination among industry participants, the exemption offers a legal mechanism to address inefficiencies without compromising core competition rules. It reflects a pragmatic shift in recognising that structural reform and economic recovery in the logistics sector require more than individual market forces can deliver.

While the exemption creates opportunities for collaboration and investment, its success will hinge on rigorous oversight by the Competition Commission to prevent anti-competitive abuse and to ensure inclusive participation by SMMEs and historically disadvantaged groups. Ultimately, if implemented with discipline and accountability, the exemption has the potential to catalyse a more efficient, resilient, and equitable logistics ecosystem, one that supports South Africa’s broader goals of economic transformation and global competitiveness.

By Matthias Bauer and Dyuti Pandya*

South Africa risks adopting the essence of the EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA), if not its exact form, with the aim of reshaping the business models of online intermediation platforms. This marks a significant shift away from the principles of traditional competition regulation.

In 2020, the Competition Commission of South Africa (CCSA) concluded that traditional enforcement tools might be inadequate to tackle structural barriers in digital markets particularly those that prevent new entrants or smaller players from expanding. This realisation led to the launch of the Online Intermediation Platforms Market Inquiry (OIPMI). By borrowing a regulatory blueprint designed for the EU, South Africa could undermine its own digital ecosystem, stifle investment, and entrench local inefficiencies. The country’s growing interest in ex ante competition regulation via the Competition Commission’s market inquiries reflects an accelerating trend of policy mimicry without consideration of domestic realities. While there is broad agreement on the need for digital competition regulation, there is little consensus on how these rules should be structured, and approaches to implementation remain highly varied across jurisdictions.

The OIPMI’s final report identified platforms such as Google, Apple, Takealot, Uber Eats, and Booking.com as dominant players distorting competition. It is claimed that, due to the significant online leads and sales these platforms generate and the high level of dependency business users have on them these scaled platforms can influence competition among businesses on the platform or exploit them through fees, ranking algorithms, or restrictive terms and conditions. However, this conclusion raises concerns about the underlying methodology. A central concern with the market inquiry approach is that it allows certain platforms to be identified as market leaders or sources of competitive distortion without requiring a formal finding of dominance, since such inquiries do not mandate that dominance be established.

The designation has been based on characteristics typically associated with globally leading technology firms. Amazon, which currently maintains only a minimal presence in South Africa, was nevertheless singled out as a potential threat to competition. It is claimed that Amazon faces similar complaints in other jurisdictions, and it is argued that fair treatment of marketplace sellers is unlikely to become a competitive differentiator capable of overcoming barriers to seller competition. Moreover, the CCSA has indicated that it would enforce the same provisions against Amazon if it were to enter the market in a way that breaches the proposed remedial measures.

Regulating for hypothetical risks while ignoring tangible consumer benefits risks becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy: global platforms may decide not to enter the market at all, leaving consumers, including small businesses and public services organisations with fewer options and slower innovation.

The OIPMI focuses on structural features that restrict competition both between platforms and among business users, facilitate the exploitation of business users, and hinder the inclusion of small enterprises and historically disadvantaged firms in the digital economy. Despite the absence of formal dominance findings, the OIPMI proposes a range of heavy-handed interventions, including the removal of price parity clauses, the introduction of transparent advertising standards, a ban on platform self-preferencing, and limitations on the use of seller data, many directly inspired by the EU DMA.

In both of CCSA’s 2022 and 2023 findings, Google Search was explicitly accused of preferential placement and distorting platform competition in South Africa. More concerning still are the CCSA’s proposed remedies in its final report- requiring targeted companies to offer free advertising space to rivals, artificially boost local competitors in search rankings, and redesign their platforms to favour smaller firms. The SACC has recommended that Google introduce identifiers, filters, and direct payment options to support local platforms, SMEs, and Black-owned businesses, and contribute ZAR150 million (around EUR 7 million) to offset its competitive advantage. For search results, Google is required to introduce a new platform sites unit (or carousel) that prominently showcases smaller South African platforms relevant to the user’s query such as local travel platforms in travel-related searches entirely free of charge. This goes beyond competition enforcement and crosses into market engineering, compelling global firms not just to compete by government decree, but to subsidise rivals and actively shape market outcomes.

In 2025, South Africa’s Competition Commission also doubled down with its provisional Media and Digital Platforms Market Inquiry (MDPMI), calling for additional remedies targeting online advertising, content distribution, and the visibility of news media. These recommendations are again influenced by EU-style regulations, particularly the EU Copyright Directive, which harms the diversity and sustainability of small news publishers. However, the report downplays South Africa’s unique institutional constraints and specific market dynamics. If adopted, the proposals would compel digital platforms to subsidise select publishers based on arbitrary and hard-to-measure assessments of news content’s value to Google’s business. This could limit access to information, hinder innovation, and monetisation efforts, ultimately narrowing consumer choice and weakening the vibrancy of the content ecosystem.

More broadly, through these market inquiries South Africa risks undermining its evolving digital economy by pursuing an approach that will deter foreign investment due to ambiguous and discretionary enforcement. At the same time, the proposed regulatory burdens could disproportionately affect domestic firms that simply lack the resources to comply. This regulatory uncertainty threatens to stifle innovation and hinder progress toward regional digital integration. In a country where corruption remains a persistent challenge, granting regulators wide discretionary powers over digital market outcomes also raises serious governance concerns. Moreover, by enforcing a narrow and politicised notion of “fairness”, South Africa risks sacrificing consumer choice and strangling the diversity of digital services that a competitive market would otherwise deliver.

Notably, coming back to the EU’s DMA, it was crafted for specific European conditions, particularly in markets where technologically-leading global platforms held relatively high market shares in many EU Member States. Yet even within the EU, the DMA remains hotly disputed – not least because it targets large non-European companies that have long been politically embraced for injecting digitisation into traditional industries and, through competition, helped European businesses and consumers benefit from technology innovation.

EU digital policies, developed from the perspective of wealthy, mature (Western) European markets, should not be assumed to be readily applicable elsewhere. South Africa’s digital markets are still in their infancy, ICT infrastructure remains unevenly developed, and regulatory institutions face significant resource constraints. Emulating the DMA – even informally – risks premature intervention, regulatory overreach, and the distortion of competitive dynamics before they have had a proper chance to emerge and mature.

Competition policy undoubtedly has a role in promoting competition. But poorly tailored rules may end up punishing the very firms that South Africa needs to scale and empower its own digital economy. Instead of replicating the EU’s Digital Markets Act, South Africa should focus on evidence-based case-by-case enforcement – grounded in its own market realities and institutional capabilities. Otherwise, South Africa risks becoming the casualty of a regulatory experiment designed for a different continent – with consequences its digital economy can ill afford.

*The authors are affiliated with ECIPE, the European Centre for International Political Economy

By Jannes van der Merwe

The African Continental Free Trade Area (“AfCFTA”) agreement, currently entered by 55 African countries, came into operation on 30 May 2019 and thereafter officially lodged in 2021. The purpose of the AfCFTA agreement is to create a single market for the continent, allowing free flow of goods and services across the continent and boost trading position of Africa in the global market[1].

While it is important to take into consideration that any change requires time, the question remains whether the AfCFTA agreement will in fact inject a positive change into Africa’s economy and promote intra-African trade.

The World bank predicts an economic growth for Africa, albeit it substantially low, indicating that the projected growth for Sub-Saharan Africa is 3% in 2024 and by 4% in 2025 to 2026, with East Africa expected to grow by 2.2% in 2024 and West Africa to grow by 3.9% in 2024.[2]

In 2023, the World bank further stated that research shows that the AfCFTA could lift 50 million people in Africa out of extreme poverty by 2035 and expand incomes by USD 571 billion[3].

Africa has been preparing itself for a growth in the Economy and the competition that comes with this in the broader African economy, by increasing regulatory infrastructure to oversee intra-African trade, with the likes of COMESA[4] and the recently functional ECOWAS[5], together with an increase of regulatory provision within African jurisdictions. ‘

However, despite the preparation and readiness for a nuclear increase of intra-African trade, various factors have been hindering the progress. Africa has been riddled with uncertainties, related to political unrest, rising conflict and violence, climate shocks and high debt distress risks[6]. This leaves market leaders cautious to invest in Africa, and African entities to trade over and across these uncertain jurisdictions.

Article 4 of the AfCFTA agreement states that the specific objectives of the agreement is to progressively eliminate tariffs and non-tariff barriers; progressively liberalise trade in services; cooperate on investments, IP and competition policy; cooperate on all trade-related areas; cooperate on customs matters and the implementation of trade facilitation measures; establish a mechanism for the settlement of disputes concerning their rights and obligations; and to establish and maintain an institutional framework for the implementation and administration of AfCFTA.

South Africa has taken a positive step in this direction, as trade under the AfCFTA commenced during January 2024 where South African entities can export on a duty free, or reduced duty, for certain products. The South African Revenue Services has implemented the AfCFTA agreement and reduced the tariffs for these products[7]. However, the responsibility remains on African entities to promote the benefits of AfCFTA by increasing the intra-African trade and making full use of the economic gain that stems from the AfCFTA agreement.

While Africa is hopeful for the positive incorporation of the specific objectives of AfCFTA and the potential economic boost that AfCFTA can incorporate, this will only come with time, cooperation by the various African jurisdictions and proper implementation of the AfCFTA agreement.

[1]See: https://www.eac.int/trade/international-trade/trade-agreements/african-continental-free-trade-area-afcfta-agreement.

[2]See: https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/overview.

[3] See: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/trade/africa-pursues-free-trade-amid-global-fragmentation.

[4] Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa.

[5] Economic Community of West African States.

[6] See fn. 2 supra.

[7] The reduced tariffs can be found at https://www.sars.gov.za/legal-counsel/secondary-legislation/tariff-amendments/tariff-amendments-2024/

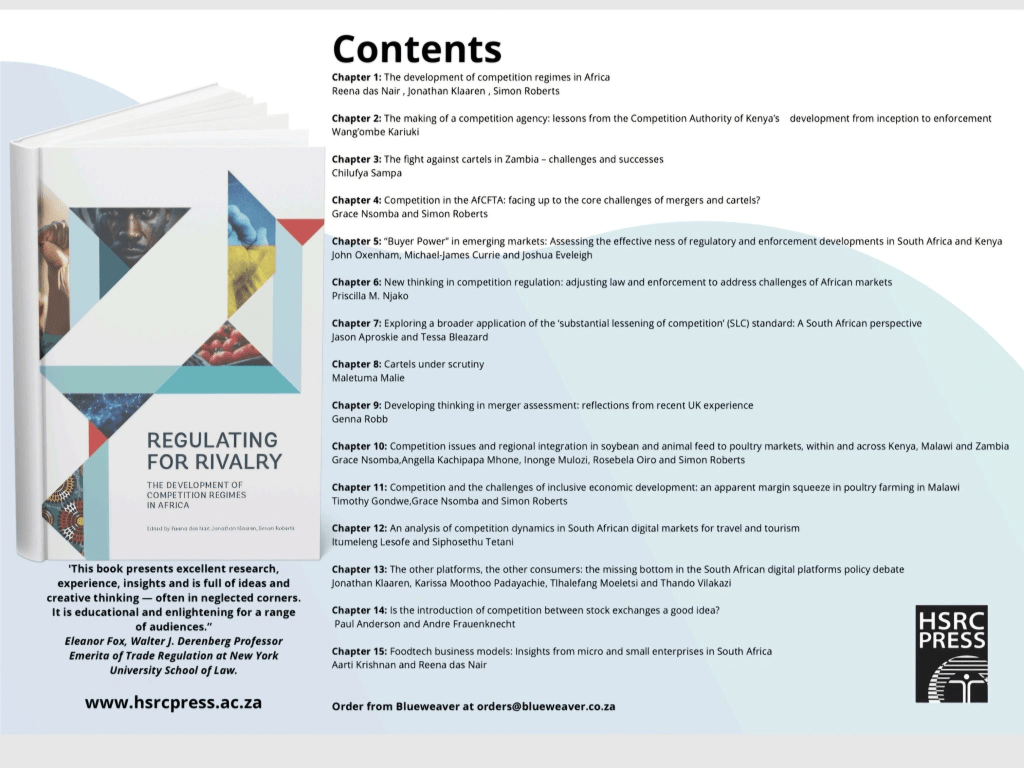

The Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development (“CCRED”) has announced the launch of its latest publication: “Regulating for Rivalry: The Development of Competition Regimes in Africa”. Co-edited by Reena das Nair, Simon Roberts, and Jonathan Klaaren, this book looks to be a comprehensive compilation of cutting-edge research and analyses, bringing together the key papers presented at previous ACER Week (Annual Competition and Economic Regulation) conferences. It also includes contributions from CCRED’s ongoing work, reflecting a rich exchange of ideas aimed at fostering competitive markets and effective regulation across the African continent.

One of the notable contributions in the book is a paper written by Primerio’s John Oxenham, Michael-James Currie, and Joshua Eveleigh, titled “Buyer Power in Emerging Markets: Assessing the Effectiveness of Regulatory Enforcement Developments in South Africa and Kenya”. This paper delves into the complex dynamics of buyer power, particularly in emerging markets, and evaluates the impact of recent regulatory enforcement efforts in South Africa and Kenya. Their research provides critical insights into the challenges and successes of regulatory buyer power within these key African economies, offering valuable lessons for policymakers and regulators across the continent.

“Regulating for Rivalry” will be available in both digital and print formats towards the end of 2024. The book is expected to be an essential resource for academics, regulators, legal practitioners, and policymakers engaged in the development and enforcement of competition law in Africa. It showcases the growing maturity and innovation of competition regimes across the continent, highlighting the critical role of effective regulation in promoting economic development and inclusive growth.