Competition Law conference provides most in-depth look at the state of Cameroonian antitrust law

Event organised by Dr. Patricia Kipiani and Prof. Tchapga of Primerio & CEMAC, the Cameroon school of business and its competition law section

What follows is an article that appeared in French in the Le Droit journal, written by Stéphane Ngoh, reprinted here with permission. An English translation is below. An interview with Dr. Kipiani related to the conference can be found here. In it, she discusses the planned creation of a “Competition Observatory” for the country.

Le cabinet Primerio International a organisé un séminaire de sensibilisation aux enjeux du droit et de la politique de la concurrence au Cameroun et dans l’espace de la CEMAC. L’évènement lancé par le ministre du Commerce, M. Luc Magloire Mbarga Atangana s’est déroulé le 7 juillet 2016 au siège du GICAM à Douala.

Le cabinet Primerio International a organisé un séminaire de sensibilisation aux enjeux du droit et de la politique de la concurrence au Cameroun et dans l’espace de la CEMAC. L’évènement lancé par le ministre du Commerce, M. Luc Magloire Mbarga Atangana s’est déroulé le 7 juillet 2016 au siège du GICAM à Douala.

Présenter la concurrence comme « un bien commun » à la collectivité et « renforcer la pédagogie de la concurrence dans ses dimensions juridiques et politiques» tels peuvent être les maitres mots du premier « rendez-vous de la concurrence» au Cameroun et en CEMAC impulsé par le cabinet d’expertise Primerio International et placé sous le thème «Du droit et de la politique de la concurrence au Cameroun et dans l’espace CEMAC ». Comme pour en souligner toute l’importance, le ministre du Commerce du Cameroun, Luc Magloire Mbarga Atangana, a fait le déplacement de la capitale économique dans l’optique d’en présider le lancement officiel. Le Docteur en droit et avocate au barreau de Bruxelles, Mme Patricia Kipiani, qui représentait le cabinet Primerio International pour l’occasion a expliqué combien cette première édition des « rendez-vous de la concurrence », se voulait sérieuse. Toute chose ayant justifié l’association aussi bien des universitaires de tous bords, du groupement inter-patronal du Cameroun (Gicam) que des autorités publiques camerounaises. Les Chercheurs de l’Université de Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne en France et les spécialistes du droit de la concurrence, le Professeur des universités Martine Behar-Touchais et l’enseignant-chercheur Laurent Vidal ont fait le déplacement du Gicam.

Le ministre du Commerce, qui intervient comme l’autorité publique de tutelle du secteur de la concurrence, a tenu à préciser que les rendez-vous de la concurrence ne pouvaient mieux tomber dans un contexte communautaire et camerounais situé à « la veille de l’entrée en vigueur des Accords de partenariat économique « APE », entre les pays ACP et l’UE dont le Cameroun est partie », ces accords qui impliquent une ouverture de l’économie imposent donc qu’un certain accent soit mis sur le droit et la politique de la concurrence. Au demeurant, le représentant de l’Etat du Cameroun à ce rendez-vous a tenu à réaffirmer la place reservée jusqu’ici à la concurrence, « notre conviction, a –t-il expliqué, est que le commerce a besoin d’un environnement sain et c’est la raison pour laquelle un arsenal des textes législatives ou règlementaires existe au Cameroun et cela témoigne de la volonté de l’état de réguler le secteur ». A l’appui de son affirmation, M. Luc Magloire Mbarga Atangana a soutenu que la volonté et la détermination du Cameroun à faire du droit de la concurrence un enjeu de poids, se traduit depuis des années. Pour s’en féliciter, il souligne que les premières velléités d’encadrement de la concurrence remontent aux années1990 et qu’autant les lois ont créé la Commission nationale de la concurrence (Cnc) autant des décrets en ont fixés les contours organisationnels et structurels. Le président de ladite Commission Léopold Boumsong, qui était dans la suite du Mincommerce, a été appelé à présenter les aspects nationaux de la concurrence et précisément le rôle de la Commission nationale de la concurrence. Ce rôle, comme l’a martelé le ministre, doit s’attacher à « poursuivre et sanctionner les pratiques anticoncurrentielles, en s’appuyant sur des textes datant et nouveau à l’instar de la loi cadre protection sur la consommation, de la nouvelle loi portant organisation des activités commerciales ainsi que la loi sur commerce extérieur ».

Le ministre du Commerce, qui intervient comme l’autorité publique de tutelle du secteur de la concurrence, a tenu à préciser que les rendez-vous de la concurrence ne pouvaient mieux tomber dans un contexte communautaire et camerounais situé à « la veille de l’entrée en vigueur des Accords de partenariat économique « APE », entre les pays ACP et l’UE dont le Cameroun est partie », ces accords qui impliquent une ouverture de l’économie imposent donc qu’un certain accent soit mis sur le droit et la politique de la concurrence. Au demeurant, le représentant de l’Etat du Cameroun à ce rendez-vous a tenu à réaffirmer la place reservée jusqu’ici à la concurrence, « notre conviction, a –t-il expliqué, est que le commerce a besoin d’un environnement sain et c’est la raison pour laquelle un arsenal des textes législatives ou règlementaires existe au Cameroun et cela témoigne de la volonté de l’état de réguler le secteur ». A l’appui de son affirmation, M. Luc Magloire Mbarga Atangana a soutenu que la volonté et la détermination du Cameroun à faire du droit de la concurrence un enjeu de poids, se traduit depuis des années. Pour s’en féliciter, il souligne que les premières velléités d’encadrement de la concurrence remontent aux années1990 et qu’autant les lois ont créé la Commission nationale de la concurrence (Cnc) autant des décrets en ont fixés les contours organisationnels et structurels. Le président de ladite Commission Léopold Boumsong, qui était dans la suite du Mincommerce, a été appelé à présenter les aspects nationaux de la concurrence et précisément le rôle de la Commission nationale de la concurrence. Ce rôle, comme l’a martelé le ministre, doit s’attacher à « poursuivre et sanctionner les pratiques anticoncurrentielles, en s’appuyant sur des textes datant et nouveau à l’instar de la loi cadre protection sur la consommation, de la nouvelle loi portant organisation des activités commerciales ainsi que la loi sur commerce extérieur ».

TROIS GRANDES PRATIQUES ANTICONCURRENTIELLES

Le président de la Cnc a précisé à l’égard des chefs d’entreprises qui emplissaient la salle du Gicam qu’il existe sommairement 3 types de pratiques qui ont « pour effet d’empêcher, de fausser ou de restreindre de manière sensible, l’exercice de la concurrence au niveau du marché intérieur » au sens de la loi n°98/013 du 14 juillet 1998 relative à la concurrence. Il s’agit des abus d’une entreprise ou d’un groupe d’entreprises en position dominante sur le marché, des fusions et acquisitions d’entreprises et aussi des accords anticoncurrentiels. L’un dans l’autre, il est apparu que les pratiques anticoncurrentielles au Cameroun sont constatées par procès-verbal dressé par les membres de la Commission suite aux enquêtes consécutives à une plainte d’une personne physique ou morale ou à celles initiées par eux-mêmes.

Le président de la Cnc a précisé à l’égard des chefs d’entreprises qui emplissaient la salle du Gicam qu’il existe sommairement 3 types de pratiques qui ont « pour effet d’empêcher, de fausser ou de restreindre de manière sensible, l’exercice de la concurrence au niveau du marché intérieur » au sens de la loi n°98/013 du 14 juillet 1998 relative à la concurrence. Il s’agit des abus d’une entreprise ou d’un groupe d’entreprises en position dominante sur le marché, des fusions et acquisitions d’entreprises et aussi des accords anticoncurrentiels. L’un dans l’autre, il est apparu que les pratiques anticoncurrentielles au Cameroun sont constatées par procès-verbal dressé par les membres de la Commission suite aux enquêtes consécutives à une plainte d’une personne physique ou morale ou à celles initiées par eux-mêmes.

Par la suite, les aspects multilatéraux de la concurrence ont été évoqués au travers de la présentation du rôle de la Conférence des Nations Unies sur le Commerce et le Développement (CNUCED) en matière l’accompagnement des politiques de concurrence. L’économiste de la CNUCED, Yves Kenfack a découvert le code CNUCED de la concurrence dont il a salué la pertinence tout en regrettant que celui-ci ne soit pas contraignant pour les Etats signataires.

Un autre moment des échanges a porté sur les aspects croisés entre le point de vue de l’économiste et celui du juriste quant à la concurrence. C’est M. Flavien Tchapga, économiste, consultant lui aussi à Primerio International et professeur associé à l’Université Senghor d’Alexandrie, qui s’y est attelé face à l’auditoire de la salle des conférences du Gicam. L’intervention de ce dernier peut se ramener à une suggestion forte faisant suite à l’interrogation suivante : « peut-on réussir la sensibilisation sur la concurrence si l’on ne tient pas compte des spécificités de l’environnement local ? ». Réponse, en effet, dans un contexte où 9 entreprises sur 10 sont individuelles, il faut se méfier des formules des juristes qui sont souvent larges et complexifiées pour les économistes plus proches du terrain.

Un autre moment des échanges a porté sur les aspects croisés entre le point de vue de l’économiste et celui du juriste quant à la concurrence. C’est M. Flavien Tchapga, économiste, consultant lui aussi à Primerio International et professeur associé à l’Université Senghor d’Alexandrie, qui s’y est attelé face à l’auditoire de la salle des conférences du Gicam. L’intervention de ce dernier peut se ramener à une suggestion forte faisant suite à l’interrogation suivante : « peut-on réussir la sensibilisation sur la concurrence si l’on ne tient pas compte des spécificités de l’environnement local ? ». Réponse, en effet, dans un contexte où 9 entreprises sur 10 sont individuelles, il faut se méfier des formules des juristes qui sont souvent larges et complexifiées pour les économistes plus proches du terrain.

Au cours du rendez-vous de la concurrence, une table-ronde a été ouverte pour asseoir la dimension didactique de la rencontre. Les débats et les questions étaient placés sous la houlette de M. Martin Abega, administrateur de sociétés, ancien membre de la Commission nationale de la concurrence et Consul honoraire du Royaume des Pays-Bas au Cameroun.

En dernière analyse, les expériences pratiques de règlementations et de politiques de la concurrence en Europe et au Cameroun ont clairement été croisées par le biais de Martine Behar-Touchais et Laurent Vidal d’une part et de Me Abdoul Bagui d’autre part. Etant entendu qu’au Cameroun, la régulation est émiettée par secteur d’activités.

Ce sont concrètement toutes les difficultés liées au libre exercice de la concurrence qui ont été passées au crible. La contrebande, la persistance des monopoles dans certains domaines ou encore la contrefaçon relèvent de ces écueils épluchés par les soins des experts internationaux et locaux à l’instar des représentants du CNUCED, de CEMAC, de l’OHADA et surtout des entreprises camerounaises. Le Dr. Patricia Kipiani a expliqué qu’il était important que « les réflexions et les échanges reviennent sur les difficultés auxquelles se heurtent les entreprises, sur les difficultés liées à la concurrence déloyale, à leur impact sur le secteur informel et autres activités informelles des entreprises formelles. Et aussi qu’ un accent soit mis sur la réglementation et sur les politiques économiques susceptibles de promouvoir notre espace économique ».

Stéphane Ngoh

For our English readers, below is a Google Translate version in English of the article:

The international firm Primerio organized an awareness seminar on issues of law and competition policy in Cameroon and in the CEMAC zone. The event launched by the Minister of Trade, Luc Magloire Mbarga Atangana Mr. took place July 7, 2016 at the headquarters of GICAM in Douala.

Introduce competition as a “common good” to the community and “strengthen the teaching of competition in its legal and political dimensions” — such are the watchwords of the first “meeting competition” in Cameroon and driven CEMAC by the consultancy firm Primerio International and under the theme “from the law and competition policy in Cameroon and in the CEMAC.” As if to emphasize the importance, the trade minister of Cameroon, Luc Magloire Atangana Mbarga, made the trip from the economic capital with a view to chair the official launch. The Doctor of Law and lawyer at the Brussels Bar, Patricia Kipiani, who represented the firm Primerio International for the occasion explained how this first edition of “appointments of competition”, was meant seriously. Anything that justified the association both academics of all stripes, the inter-group employers of Cameroon (Gicam) that the Cameroonian public authorities. The researchers from the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne in France and specialists from the competition law, the University Professor Martine Behar-Touchais and Laurent Vidal teacher-researcher made the trip from Gicam.

Minister of Commerce, which acts as a public authority supervising the sector to competition, has insisted that the appointment of the competition could not get better in a community and Cameroonian context located “on the eve of the entry into force of the economic partnership agreements ‘EPAs’, between the ACP countries and the EU which Cameroon is a party “, these agreements which involve opening up the economy therefore require that a certain emphasis on law and the competition policy. Moreover, the representative of the State of Cameroon to this appointment held to reaffirm the place reserved far in the competition, “our conviction has -t he explained, is that the trade needs a healthy environment and that is why an arsenal of legislative and regulatory texts exist in Cameroon and it demonstrates the willingness of the state to regulate the sector. “ In support of its contention, Luc Magloire Atangana Mbarga argued that the will and determination of Cameroon to the competition law of a weight issue, resulting in years. To be welcomed, he stressed that the first framework for competition ambitions date back to the 1990’s and that so many laws created the National Competition Commission (CNC) as decrees have laid the organizational and structural contours. The president said Leopold Commission Boumsong, who was later in the MINCOMMERCE, was called to present the national aspects of competition and specifically the role of the National Competition Commission. This role, as insisted the minister, must strive to “prosecute and punish anti-competitive practices, based on texts dating and new like the law under protection on consumption, the new law on the organization of business and the foreign trade Act. “

THREE MAJOR ANTI-COMPETITIVE PRACTICES

The president of the CNC said against business leaders who filled the room Gicam there summarily 3 types of practices which have “the effect of preventing, distorting or restricting significantly, the year of competition in the internal market “under law No. 98/013 of 14 July 1998 on competition. This is abuse of a company or group of companies in a dominant market position, mergers and acquisitions as well as anti-competitive agreements. One the other, it appeared that anti-competitive practices in Cameroon are recorded in minutes drawn up by the Commission of the members following the investigations following a complaint from a natural or legal person or those initiated by them -Same.

Thereafter, the multilateral aspects of competition were discussed through the presentation of the role of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in support for competition policy. The economist of UNCTAD, Yves Kenfack discovered the UNCTAD code of competition which he praised the relevance while regretting that it was not binding on the signatory states.

Another moment of trade covered the Crusaders aspects between the views of the economist and that of the lawyer about the competition. It was Mr. Flavien Tchapga, economist, consultant also to Primerio International and associate professor at the Senghor University of Alexandria, which it is harnessed facing the audience of the Gicam conference room. The intervention of the latter can be reduced to a strong suggestion in response to the following question: “can we succeed awareness on competition if it does not take into account the specificities of the local environment? “. Response, in fact, in a context where 9 out of 10 companies are individual, beware formulas lawyers who are often larger and more complex to the nearest economists ground.

During the appointment of the competition, a panel discussion was opened to establish the educational dimension of the encounter. The debates and issues were under the leadership of Mr. Martin Abega, corporate director, former member of the National Competition Commission and Honorary Consul of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Cameroon.

Ultimately, the practical experiences of regulations and competition policies in Europe and Cameroon have clearly been crossed through Martine Behar-Touchais and Laurent Vidal one hand and Mr. Abdul Bagui other. It being understood that in Cameroon, regulation is broken by sector.

These are all practical difficulties related to the free exercise of competition that were screened. Smuggling, the persistence of monopolies in certain areas or counterfeiting within these pitfalls peeled for the service of international and local experts like the representatives of UNCTAD, CEMAC, OHADA and especially Cameroonian companies. Dr. Patricia Kipiani said it was important that “the reflections and exchanges back on the difficulties firms face, the difficulties related to unfair competition, their impact on the informal sector and other informal activities formal businesses. And also that an emphasis on regulation and economic policies that promote our economic space. “

In terms of the AMSA settlement agreement, AMSA admitted to contravening the cartel provisions contained in the Competition Act and agreed to pay a R1.5 billion (in instalments of no less than R300 million per annum for five years) administrative penalty. In addition to the administrative penalty, AMSA also agreed to invest approximately R4,6 Million into the South African economy for the next 5 years (provided the prevailing economic conditions render such investment feasible) by way of CAPEX obligations.

In terms of the AMSA settlement agreement, AMSA admitted to contravening the cartel provisions contained in the Competition Act and agreed to pay a R1.5 billion (in instalments of no less than R300 million per annum for five years) administrative penalty. In addition to the administrative penalty, AMSA also agreed to invest approximately R4,6 Million into the South African economy for the next 5 years (provided the prevailing economic conditions render such investment feasible) by way of CAPEX obligations. While settlement negotiations are inherently flexible, it is important that agencies ensure an objective and a transparent methodology in the manner in which they approach the quantification of a settlement agreement. This has certainty been strived for by the Competition Commission when it elected to publish Guidelines on the Determination of the Calculation of Administrative Penalties (Guidelines). The objectives of the Guidelines, may however, be undermined in light of the broader behavioural and public interest related conditions imposed in recent cases.

While settlement negotiations are inherently flexible, it is important that agencies ensure an objective and a transparent methodology in the manner in which they approach the quantification of a settlement agreement. This has certainty been strived for by the Competition Commission when it elected to publish Guidelines on the Determination of the Calculation of Administrative Penalties (Guidelines). The objectives of the Guidelines, may however, be undermined in light of the broader behavioural and public interest related conditions imposed in recent cases.

x-brand chemicals. The Commission has invited “general public and stakeholders” for comments according to its formal statement.

x-brand chemicals. The Commission has invited “general public and stakeholders” for comments according to its formal statement.

The web of MoU’s recently concluded, which have as their primary objectives the facilitation of information exchanges and cooperation between competition agencies, is certainly a significant stride made to assist the authorities, including the CCC, in detecting and prosecuting anticompetitive practices which may be taking place across the African continent.

The web of MoU’s recently concluded, which have as their primary objectives the facilitation of information exchanges and cooperation between competition agencies, is certainly a significant stride made to assist the authorities, including the CCC, in detecting and prosecuting anticompetitive practices which may be taking place across the African continent.

Professional fees for advocates in Kenya are set by the Chief Justice under the Advocates Act Chapter 16 of the Laws of Kenya. Part IX Section 44 provides that the Chief Justice may by order prescribe and regulate in such manner as he/she thinks fit the remuneration of advocates in respect of all professional business, whether contentious or non-contentious. Sub-section (2) also provides that the Chief Justice may prescribe a scale of rates of commission or percentage in respect of non-contentious business.

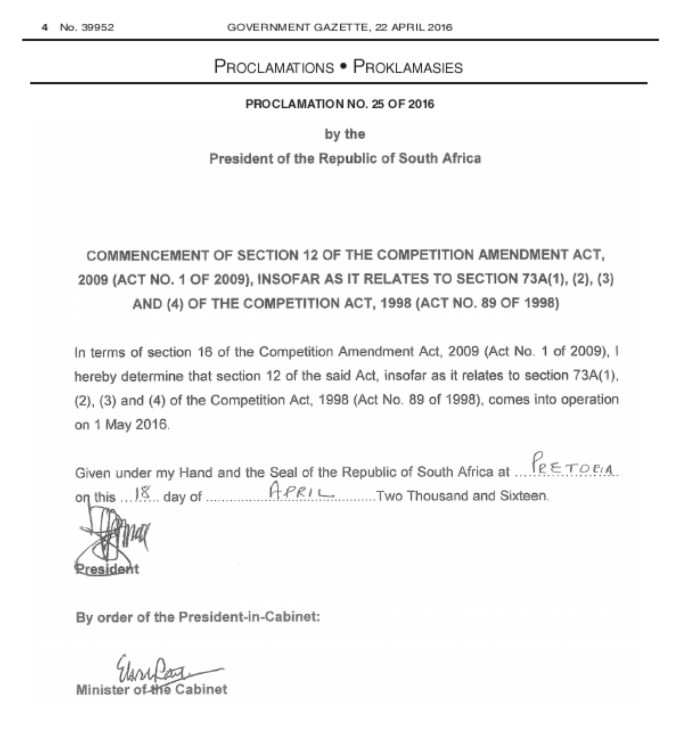

Professional fees for advocates in Kenya are set by the Chief Justice under the Advocates Act Chapter 16 of the Laws of Kenya. Part IX Section 44 provides that the Chief Justice may by order prescribe and regulate in such manner as he/she thinks fit the remuneration of advocates in respect of all professional business, whether contentious or non-contentious. Sub-section (2) also provides that the Chief Justice may prescribe a scale of rates of commission or percentage in respect of non-contentious business. We are referring to the “phased” implementation of the 2009

We are referring to the “phased” implementation of the 2009  According to news reports, Mr. Patel announced today (Thursday), that the criminalisation of the price-fixing cartel offence would henceforth be enforced. Section 73A will be gazetted tomorrow, 22 April 2016, and hold the force of law from 1 May 2016. BDLive also

According to news reports, Mr. Patel announced today (Thursday), that the criminalisation of the price-fixing cartel offence would henceforth be enforced. Section 73A will be gazetted tomorrow, 22 April 2016, and hold the force of law from 1 May 2016. BDLive also  We live in the era of the

We live in the era of the