By AAT Senior Contributor, Michael-James Currie & Mweshi Mutuna, Pr1merio competition advocate (Zambia)

The Zambian Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (‘CCPC’) has recently published draft settlement guidelines (‘Draft Guidelines’) for respondents who have allegedly engaged in conduct in contravention of the domestic Competition and Consumer Protection Act (‘Act’).

The Draft Guidelines have been published in addition to the ‘Leniency Programme’ as well as the ‘Fines Guidelines’ published earlier this year (as well as the 2015 Merger Guidelines), and essentially sets out a framework within which respondent parties may engage the CCPC for purposes of reaching a settlement agreement for alleged contraventions of the Act.

The Draft Guidelines have been published in addition to the ‘Leniency Programme’ as well as the ‘Fines Guidelines’ published earlier this year (as well as the 2015 Merger Guidelines), and essentially sets out a framework within which respondent parties may engage the CCPC for purposes of reaching a settlement agreement for alleged contraventions of the Act.

Notably, the Draft Guidelines will be binding on the CCPC which is an important aspect of ensuring a transparent and objective approach to settlement negotiations. Furthermore, the Draft Guidelines emphasise that respondents should be fully informed of the case against them prior to settling. In this regard, the Draft Guidelines provide for an initial stage of the settlement negotiations (essentially an expression of interest) which follows from a formal request by a firm expressing an interest to settle.

Should the CCPC decide to proceed with settlement negotiations, the CCPC must, within 21 days, provide the respondent party with information as to the nature of the case against the respondent. This includes disclosing the alleged facts and the classification of those facts, the gravity and duration of the alleged conduct, the attribution of liability (which we discuss further below) and the evidence relied on by the CCPC to support the complaint.

The authors, Mr. Currie & Ms. Mutuna

The authors, Mr. Currie & Ms. MutunaThe purpose of disclosing these facts to a respondent is to afford a respondent the opportunity to meaningfully consider and evaluate the case against it in order to make an informed decision whether to settle or not.

Assuming that an expression of interest in settling the matter is established by both parties, the CCPC will then proceed by requesting that the respondent provide a formal “settlement submission” within 15 days of the CCPC’s request. Included in the settlement submission, must be a clear and unequivocal acknowledgement of liability (which includes a summary of the pertinent facts, duration and the respondent’s participation in the anticompetitive conduct) and the maximum settlement quantum which the respondent is prepared to pay by way of an administrative penalty.

Should the CCPC accept the settlement submission, the CCPC will then commence with drafting and ultimately publishing a statement of objections (‘SO’) which essentially captures the material terms of the settlement submission. This is largely a necessary procedural step although the respondent party may object to the SO should it not correctly record the terms of the settlement agreement.

Following the publication of the SO, the CCPC will, subject to any challenges to the SO, proceed formally to make the settlement agreement a final decision as required by the Act.

Risky Business?

The above framework appears to be relatively straightforward and balanced, assuming that the parties in fact do reach a settlement agreement. The position is somewhat different in the event that settlement negotiations breakdown, particularly if the negotiations are already at a relatively advanced stage.

Most notably, settlement negotiations in terms of the Draft Guidelines are not conduced on a “without prejudice” basis. To the contrary, the Draft Guidelines states that the CCPC has the right to adopt a SO which does not reflect the parties’ settlement submission. In this event, the normal procedures for investigating and prosecuting a complaint as set out in the Act will apply.

In the event that the CCPC elects not to accept a settlement submission submitted by a respondent, the Draft Guidelines specifically state that “the acknowledgements provided by the parties in the settlement submission shall not be withdrawn and the Commission reserves the right to use the information submitted for its investigation”.

This paragraph is controversial as it places a substantial risk on a party making a settlement submission with no guarantee that the settlement proffer will be accepted by the CCPC, while at the same time, the respondent party exposes itself by making admissions which may be used against it in the course of a normal complaint investigation and determination by the CCPC.

Whether or not the financial incentive to respondents would entice a respondent to, nonetheless, engage in settlement discussions in terms of the Draft Guidelines is sufficient, only time will tell. In this regard, however, the Draft Guidelines state that a firm who settles with the CCPC prior to the matter being referred to the Board will be limited to a maximum penalty of up to 4% of the firm’s annual turnover. Should the firm settle after the matter has been referred to the Board, the maximum penalty will be capped at 7% of the firm’s annual turnover.

Multi-Party Settlements: the More the Better?

A further interesting and rather novel aspect to the Draft Guidelines is the provision made for tripartite settlement negotiations. In this regard, the Draft Guidelines cater for a rather unusual mechanism by which multiple respondents in relation to the same investigation may approach the CCPC for purposes of reaching a settlement agreement.

Although referred to as “tripartite” negotiations, the Draft Guidelines state that when the CCPC initiates proceedings against two or more respondents, the CCPC will inform a respondent of the other respondents to the complaint. Should the respondent parties collectively wish to enter into settlement negotiations, the respondents should jointly appoint a duly authorised representative to act on their behalf. In the event that the respondent parties do settle with the CCPC, the fact that the respondents were represented by a jointly appointed representative will not prejudice them insofar as the CCPC making any finding as to the attribution of liability between the respondents is concerned.

While joint representation may be suitable in the case of merger-related offences (which may have been what was envisaged by the drafters hence the reference to “tripartite” negotiations), we believe that it is hard to imagine that the drafters anticipated that, should respondents to a cartel be invited to settle the complaint against them, the cartelists would then be required to embark on further collaborative efforts: this time to engage collectively in formulating a settlement strategy and decide how they are ultimately going to ‘split the bill’ should a settlement agreement be reached.

The issue of a multi-party settlement submission is further complicated in the event that a settlement proffer is not accepted by the CCPC following a multiparty settlement submission. As mentioned above, the settlement submission must contain an admission of liability which, in the case of cartel conduct, would invariably amount to the parties to the settlement proposal admitting to engaging in cartel conduct by fixing prices or allocating markets, by way of example, between each other.

Although, the Draft Guidelines is a welcome endeavour to provide respondents with a transparent and objective framework to utilise when engaging with the CCPC for purposes of reaching a settlement, the uncertainty and risk which flows from a rejection of the settlement proffer may prove to be an impediment in achieving the very objectives of the Draft Guidelines.

In this regard, we understand that the CCPC is currently considering revised guidelines which hopefully address the concerns raised above.

The Competition Authority of Kenya (CAK) has recently announced that a number of proposed amendments to the Competition Act are currently pending before the National Assembly for consideration and approval.

The Competition Authority of Kenya (CAK) has recently announced that a number of proposed amendments to the Competition Act are currently pending before the National Assembly for consideration and approval. The Federal Republic of Nigeria is currently in the process of enacting a competition law, including to criminalise cartel activity amongst competitors. While such is in line with moves made by various other jurisdictions and theories of ‘rational actor’, sanction and deterrence, on ground realities suggest that criminalisation where transplanted might be seriously flawed.

The Federal Republic of Nigeria is currently in the process of enacting a competition law, including to criminalise cartel activity amongst competitors. While such is in line with moves made by various other jurisdictions and theories of ‘rational actor’, sanction and deterrence, on ground realities suggest that criminalisation where transplanted might be seriously flawed. intervention, thereby complementing stretched law enforcement efforts.

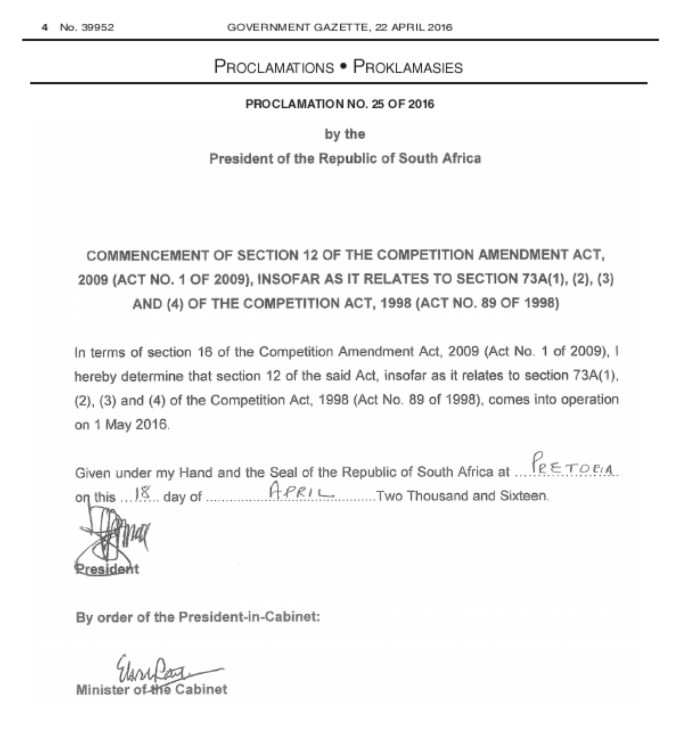

intervention, thereby complementing stretched law enforcement efforts. We are referring to the “phased” implementation of the 2009

We are referring to the “phased” implementation of the 2009  According to news reports, Mr. Patel announced today (Thursday), that the criminalisation of the price-fixing cartel offence would henceforth be enforced. Section 73A will be gazetted tomorrow, 22 April 2016, and hold the force of law from 1 May 2016. BDLive also

According to news reports, Mr. Patel announced today (Thursday), that the criminalisation of the price-fixing cartel offence would henceforth be enforced. Section 73A will be gazetted tomorrow, 22 April 2016, and hold the force of law from 1 May 2016. BDLive also  We live in the era of the

We live in the era of the

AAT does not yet know exactly what the nature and scope of the proposed amendments are, although the NaCC has indicated that the current Act, which was promulgated in 2003, is out of date and does not sufficiently cater for Namibia’s context (relating both to Namibia’s economic and socio-economic environment).

AAT does not yet know exactly what the nature and scope of the proposed amendments are, although the NaCC has indicated that the current Act, which was promulgated in 2003, is out of date and does not sufficiently cater for Namibia’s context (relating both to Namibia’s economic and socio-economic environment). ZA: The integration of stakeholders’ comments by the Competition Commission

ZA: The integration of stakeholders’ comments by the Competition Commission The South African competition authorities were established as a package of reforms to transform the unequal South African economy to make it economy inclusive and ensuring that those who participate in it are competitive.

The South African competition authorities were established as a package of reforms to transform the unequal South African economy to make it economy inclusive and ensuring that those who participate in it are competitive.

overnments of these economies have sometimes adopted a protectionist approach for key sectors of their economies in the public interest. As much as this has often contributed to the substantial lessening of competition in the affected sectors to the detriment of consumers, these regulatory measures have been upheld by the respective governments on the grounds of national interest. The EAC, however, has been very cautious in its provisions for exemptions within the common market that could contribute to the substantial lessening of competition.

overnments of these economies have sometimes adopted a protectionist approach for key sectors of their economies in the public interest. As much as this has often contributed to the substantial lessening of competition in the affected sectors to the detriment of consumers, these regulatory measures have been upheld by the respective governments on the grounds of national interest. The EAC, however, has been very cautious in its provisions for exemptions within the common market that could contribute to the substantial lessening of competition.