By DWA co-founder and visiting AAT author, Amine Mansour* (re-published courtesy of Developing World Antitrust’s editors)

When talking about competition law and poverty alleviation, we may intuitively think about markets involving essential needs. The rise of new sectors may however prompt competition authorities to turn their attention away from these markets. One of those emerging sectors is the digital economy sector. This triggers the question of whether the latter should be a top priority in competition authorities’ agenda. The answer remains unclear and depends mainly on the potential value added to consumers in general and the poor in particular[1].

Should competition authorities in developing countries focus on digital markets?

Obviously, access to computer and technology is not a source of poverty stricto sensu. In the absence of basic needs, strategies focusing on digital sectors may prove meaningless. In practice, the last thing people living in extreme poverty will think about is gaining digital skills. Their immediate needs are embodied in markets offering goods and services which are basic necessities. The approach put forward by several Competition authorities in developing countries corroborates this view. For instance, in South Africa, digital markets are not seen as a top priority. Instead, the South African competition authority focuses on food and agro-processing, infrastructure and construction, banking and intermediate industrial products.

There are however compelling arguments to be made against such position. Most importantly, although access to technology and computers is not a source of poverty, such an access can be a solution to the poverty problem. In fact, closing the digital gap by providing digital skills and making access to technology and Internet easier can help the low income population when acting either as entrepreneurs or consumers. In both cases competition law can play a decisive role.

The low income population acting as consumers

First, when acting as consumers, people with low income can enjoy the benefits of new technology-based entrant. Thanks to lower costs of operation, lower barriers to entry and (almost) infinite buyers, these new operators have changed the competitive landscape by aggressively competing against traditional companies. These features have helped them not only extending existing products and services to low-income consumers but also making new ones available for them. Better yet, in some cases increased competition coming from technology-based companies motivates traditional business forms to adapt their offer to low-income consumers so as to face this new competition and remedy shrinking revenues. Perhaps, the most noteworthy aspect of all these evolutions, is that these new entrants have, in some instances, been able to challenge incumbents’ position by driving prices downward to levels unattainable by traditional companies without scarifying their profitability.

A shining example of all this dynamic is the possibility for low-income consumers to engage, thanks to some mobile companies, in financial transaction without the need to pass through the traditional stationary banking infrastructure. For instance, in Kenya, M-PESA a mobile money transfer service that has over 22 million subscribers[2] and around 40,000 agents (around 2600 Commercial bank branches)[3] changed the life of million of citizens. The service enables clients to deposit cash into their M-PESA accounts, send or transfer money to any other mobile phone user, withdraw cash and complete other financial transactions. A farmer in a remote area in Kenya can send or receive money by simply using his mobile phone. In this way, M-PESA can act as a substitute to personal bank accounts. This experience shows how the digital economy helps overcoming the prohibitive costs of reaching low-income customers and thus raising living standards.

On that basis, we can easily imagine the counter-argument incumbent companies might put forward. In this regard, unfair competition and the need for regulation to preserve policy objectives are often in the forefront. However, there is a great risk that these arguments are simply used to restrict market entry and impede competition from those new players.

In fact, this kind of arguments do not always reflect market reality. For example, in some remote geographic areas, traditional companies and the new ones based on the digital/internet space do not even compete directly against each other. Accordingly, regulation intended to protect policy goals has no role to play given that the affected consumers are out of the reach of the traditional business. In the M-PESA example, it may be possible to argue that any operator engaging in financial transactions should observe the regulatory restrictions that apply to the banking sector in order to ensure that policy objectives such as the stability of the banking system or the protection of consumer savings are preserved. However, applying such a reasoning will leave a large part of consumers with no alternative given the absence of a banking infrastructure in remote areas. The unfair competition and regulation arguments may only hold in cases where consumers are offered alternatives capable of providing an equivalent service.

This shows the need to proceed cautiously by favoring an evidence-based approach to the ex-post use of the regulation argument by incumbent operators. This is however only one of different facets of the interaction between the competitive impact of companies based on the internet-space, the regulatory framework and the repercussions for people with low income[4].

The low income population acting as entrepreneurs

Second, the focus on digital markets as way to alleviate poverty is further justified when low-income people act as entrepreneurs. In fact, digital markets are distinguished from basic good markets in that they may act as an empowering instrument that encourages entrepreneurship.

More precisely, the digitalization of the economy results in an improved access to market information which in turn may benefit entrepreneurs especially the poor whether they intervene in the same market or in a different one. Practice is replete with cases where, for instance, a downstream firm heavily relies for its production/operation on services or products offered by an upstream company operating in a digital market. Similarly, in a traditional and somewhat caricatural way, a small-scale farmer may use VOIP calls to obtain market information or directly contact buyers suppressing the need for a middleman.

However, we can well imagine the disastrous consequences for these small-scale farmers or the downstream firm if mobile operators decide to block access to internet telephony services such as Skype or WhatsApp based on cheap phone calls using VOIP (this is what actually happened in Morocco). In such a case, the digitalization of the economy has clearly contributed to greatly lowering the costs of communication and distribution. However, low income entrepreneurs are prevented from benefiting of these low costs, which are a key input to be able to compete in the market.

The major difficulty here lies in the fact that, when low income people act as entrepreneurs, it is likely that they organize their activities in small structures. This result in relationships and structures favorable to the emergence of exploitative abuses. Keeping digital markets clear from obstructing anticompetitive practices is thus indispensable to ensure that small existing or potential competitors are not prevented from competing. This might not be easily achieved given that competition authorities’ focus is sometimes more on high profile cases.

*Co-editor, Developing World Antitrust

[1] Intervention may also be justified by the institutional significance argument. This significance lies in the fact that those markets are growing ones and challenging the common ways of both doing business and applying competition rules which in turn make it crucial for authorities to intervene by drawing the lines that ensure the right conditions for those market to grow and develop.

[2] http://www.safaricom.co.ke/about-us/about-safaricom

[3] http://www.safaricom.co.ke/personal/m-pesa/get-started-with-m-pesa/m-pesa-agents

[4] For instance, it possible to think of the same problem from an ex-ante point of view highlighting incumbent firms’ efforts to block any re-examination of the regulatory standards that apply to the concerned sector (no relaxation of the quantitative and qualitative restrictions). This aspect has more to do with the advocacy function of competition authorities.

According to the South African Competition Commissioner, Mr Tembinkosi Bonakele, the MoU creates a framework for cooperation enforcement within the SADC region. “The MoU provides a framework for cooperation in competition enforcement within the SADC region and we are delighted to be part of this historic initiative,” said Bonakele.

According to the South African Competition Commissioner, Mr Tembinkosi Bonakele, the MoU creates a framework for cooperation enforcement within the SADC region. “The MoU provides a framework for cooperation in competition enforcement within the SADC region and we are delighted to be part of this historic initiative,” said Bonakele.

From a procedural aspect, the SACC’s recommendations are made to the South African Competition Tribunal, the adjudicative body ultimately responsible for approving a merger.

From a procedural aspect, the SACC’s recommendations are made to the South African Competition Tribunal, the adjudicative body ultimately responsible for approving a merger. The latest deal struck with Patel follows the R1 billion commitment from the merging parties in the SABMiller/AB-Inbev merger less than a month ago.

The latest deal struck with Patel follows the R1 billion commitment from the merging parties in the SABMiller/AB-Inbev merger less than a month ago. The commitment made by the merging parties to the SAB/Coca-Cola merger, which was filed at the Competition Commission in March 2015, comes after the Competition Commission itself recommended that the merger be approved subject to an agreed R150 million development fund to help train and support historically disadvantaged farmers and suppliers. Despite the agreement reached with the Competition Commission and a confirmed hearing in May 2016 (effectively 14 months after the proposed transaction was filed) the merging parties have recognised the risk of further delays should Minster Patel intervene during the hearing proceedings.

The commitment made by the merging parties to the SAB/Coca-Cola merger, which was filed at the Competition Commission in March 2015, comes after the Competition Commission itself recommended that the merger be approved subject to an agreed R150 million development fund to help train and support historically disadvantaged farmers and suppliers. Despite the agreement reached with the Competition Commission and a confirmed hearing in May 2016 (effectively 14 months after the proposed transaction was filed) the merging parties have recognised the risk of further delays should Minster Patel intervene during the hearing proceedings. Minister Patel has expressed his satisfaction with the two ‘agreements’ as it is in line with his express commitment to target multinational deals, in particular, in order to promote government’s industrial policies and socio-economic objectives.

Minister Patel has expressed his satisfaction with the two ‘agreements’ as it is in line with his express commitment to target multinational deals, in particular, in order to promote government’s industrial policies and socio-economic objectives. The Federal Republic of Nigeria is currently in the process of enacting a competition law, including to criminalise cartel activity amongst competitors. While such is in line with moves made by various other jurisdictions and theories of ‘rational actor’, sanction and deterrence, on ground realities suggest that criminalisation where transplanted might be seriously flawed.

The Federal Republic of Nigeria is currently in the process of enacting a competition law, including to criminalise cartel activity amongst competitors. While such is in line with moves made by various other jurisdictions and theories of ‘rational actor’, sanction and deterrence, on ground realities suggest that criminalisation where transplanted might be seriously flawed. intervention, thereby complementing stretched law enforcement efforts.

intervention, thereby complementing stretched law enforcement efforts. The MoU creates positions of “desk officers” in each agency to ensure that the institutions will cooperate on investigations and share relevant information to ensure enforcement. It also foresees policy coordination, technical assistance and capacity-building programs.

The MoU creates positions of “desk officers” in each agency to ensure that the institutions will cooperate on investigations and share relevant information to ensure enforcement. It also foresees policy coordination, technical assistance and capacity-building programs.

CCC Chief Executive Officer George Lipimile emphasised the need to create jobs and “link industries,” as well as explain the agency’s mission: “We are going to work hard so that competition laws make sense to the people, because a law that does not benefit people is useless.”

CCC Chief Executive Officer George Lipimile emphasised the need to create jobs and “link industries,” as well as explain the agency’s mission: “We are going to work hard so that competition laws make sense to the people, because a law that does not benefit people is useless.”

Professional fees for advocates in Kenya are set by the Chief Justice under the Advocates Act Chapter 16 of the Laws of Kenya. Part IX Section 44 provides that the Chief Justice may by order prescribe and regulate in such manner as he/she thinks fit the remuneration of advocates in respect of all professional business, whether contentious or non-contentious. Sub-section (2) also provides that the Chief Justice may prescribe a scale of rates of commission or percentage in respect of non-contentious business.

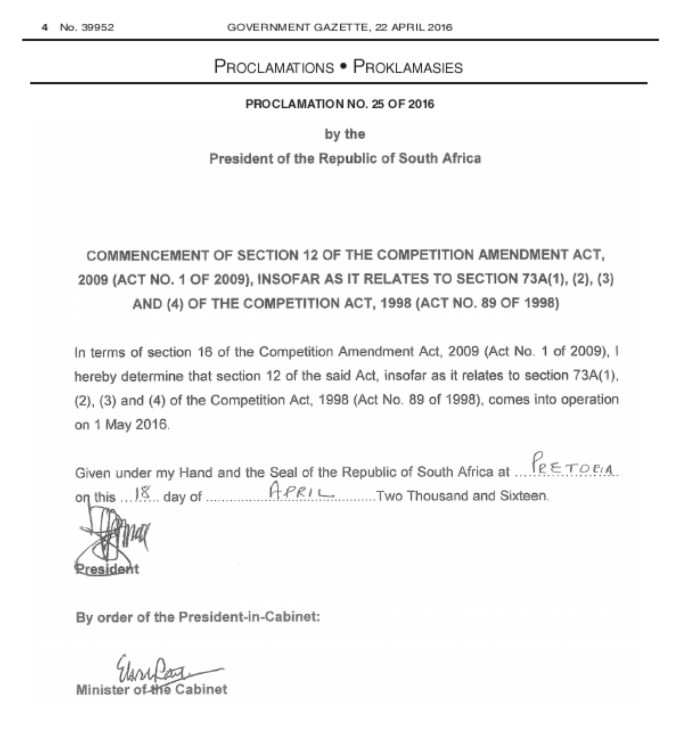

Professional fees for advocates in Kenya are set by the Chief Justice under the Advocates Act Chapter 16 of the Laws of Kenya. Part IX Section 44 provides that the Chief Justice may by order prescribe and regulate in such manner as he/she thinks fit the remuneration of advocates in respect of all professional business, whether contentious or non-contentious. Sub-section (2) also provides that the Chief Justice may prescribe a scale of rates of commission or percentage in respect of non-contentious business. We are referring to the “phased” implementation of the 2009

We are referring to the “phased” implementation of the 2009  We live in the era of the

We live in the era of the